The Bhutan-China relationship was mostly perceived as sandwiched between China and India, but no more. Bhutan is no more India’s pet in dealings and connections. With perennial road connectivity between Bhutan and China, Bhutan is no longer India-locked. Now, Bhutan has a second country to drive in and out without having to go through India.

China had been teasing India at the Doklam Plateau in Bhutan’s west, and the three countries make spring news when the Chinese soldiers come south of the Himalayas to the sensitive trijunction every year. When the reporters, news media, and politicians were busy exchanging volleys of accusations, the governments of Bhutan and China were silently working in the disputed Pasamlung and Jakarlung regions connecting the two countries with perennial roads. Both Pasamlung and Jakarlung regions were under dispute between the two neighbours.

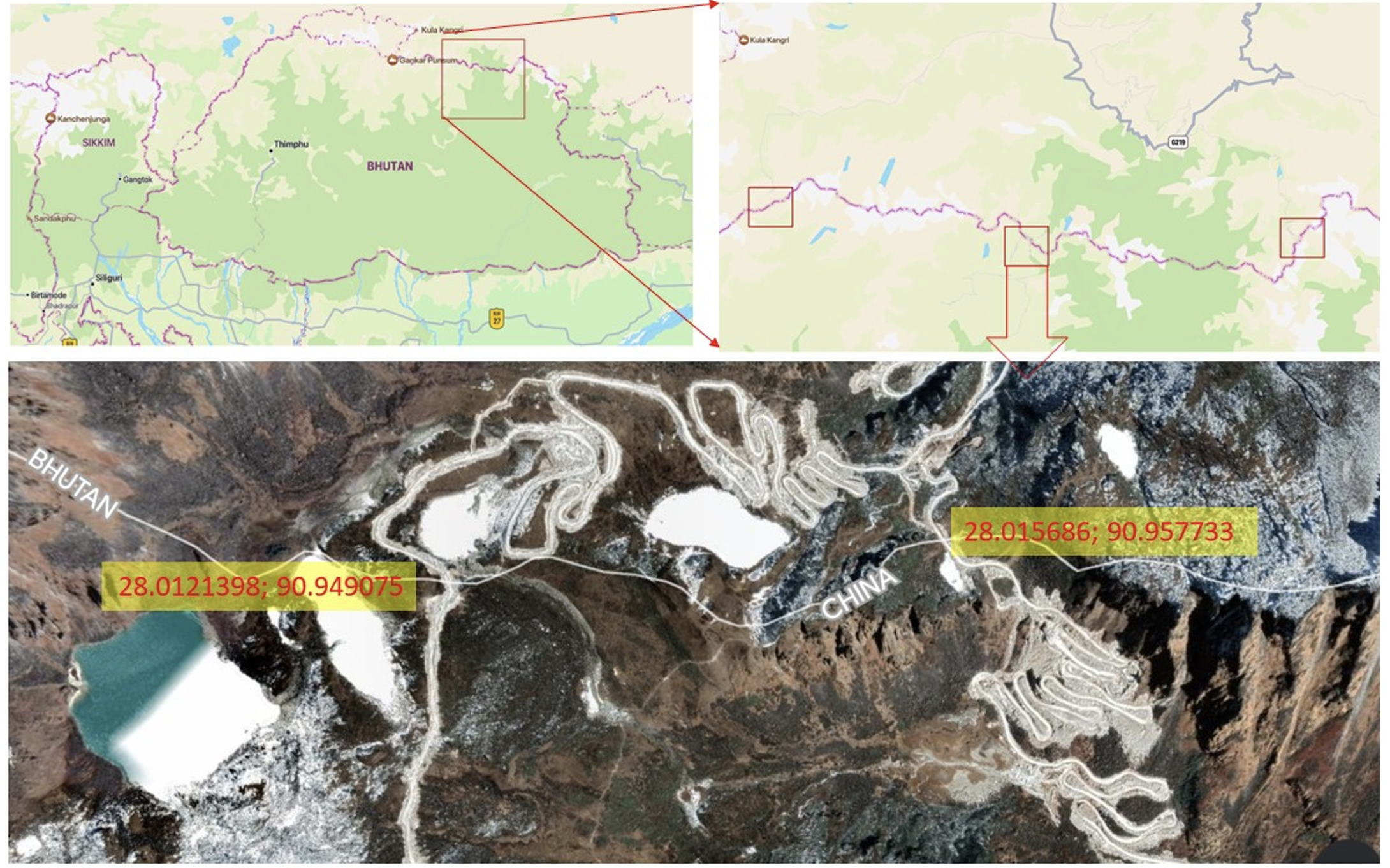

Today, Bhutan’s Lhuentse District and China’s Lhodruk County are connected by newly constructed highways.

Now Bhutan roads connect to two Chinese highways: Lajie Highway and Xincangpo Highway. On the Bhutan side, the highways get Drukpa names Jakarlung Highway and Lagyap Highway.

The two highways cross the international border at coordinates 28.0121398N, 90.949075 E (Lajie Highway China or Lagyap Highway Bhutan) and 28.015686N and 90.957733 E (Xincangpo Highway China and Jakarlung Highway Bhutan). Roads from China have reached the Bhutan border at two other points, one road is heading towards Bumthang District and the other Gongla Highway has reached the border of Tashiyangtse District. The Chinese Road has reached the border of Tashiyangtse District at 28.014406 N and 91.280827 E. This wait for a crossover could be to evaluate the situation and response.

With these land intrusions from China, the remote districts of Luntse, Tashi Yangtse and Bumthang will have road access to the outside world.

Although Lhuentse District of Bhutan and Lhodruk County of Tibet are recently connected by roads, the people on the two sides of the borderline share historical linkages. Lhodruk is one of the counties of Shannon Prefecture that was the centre of the civilisation of the Lho people. Most Drukpas of Central and Eastern Bhutan are descendants of the Lho people. The northern land of present-day Bhutan was known by the name Lho Mon. The people on the two sides share blood and conjugal relations but their connection was truncated in 1959 after China took over Tibet. The roads will reconnect the truncated relationships.

Much of the discontent between Bhutan and China was in seven regions along the Bhutan-China border (See: Bhutan-China Border Mismatch). The final negotiation was stalled at the land swap between Doklam and Pasamlung. China had agreed to give Bhutan 495 Km2 of controversial land at Pasamlung, in return Bhutan had to leave 269 km2 of the controversial region at Doklam. Out of the disputed 269 km2 of Doklam, China was interested in its 100 km2 plateau.

Doklam being sensitive to its regional security, India was the hindrance in the land-swap deal. The two governments always kept the deals silent and away from the media.

In 2007, Bhutan unceremoniously ceded its northern rhino-horn region of mountainous land including its tallest Kulakangri to China.

The road connectivity gives multiple advantages to Bhutan, yet opens doors of fear to India. As the Bhutan government updates India on its every move, it is not clear if the road connectivity was under New Delhi’s green signal.

Even if Bhutan missed updating its southern neighbour, or is in process, the Bhutan India Treaty updated in 2007 that replaced the 1949 treaty, no longer necessitates Bhutan to seek India’s guidance in its foreign policy matters. As per the 2007 updated treaty, Bhutan must inform India only when it must import weapons from any country outside India through India.

The rulers in Bhutan could be testing the spirit of the 2007 treaty. Besides, India has stationed General Reserve Engineer Force (GREF), its project DANTAK, and Indian Military Training Team (IMTART) all over Bhutan for security, road construction, and surveillance. During the Covid Pandemic, the movement of the Indian people working in the country was severely restricted. In Lhuntse, a national surveillance check post with the name Wangchuck Centennial National Park (WCNP) was activated that regulated the movement of people going towards China border.

Every time Thimphu leaders show their intimacy with China, New Delhi teaches them a lesson. The latest acid test was in 2013 when a photograph of the then Prime Minister of Bhutan shaking the hands of his Chinese counterpart during an international conference in Brazil was released to the media. The Bhutanese PM was expected to inform or update his counterparts in Delhi but had ignored it. The government of India slashed the subsidies it was providing to Bhutan on the eve of the national election. The Indian intervention had an immediate effect. The ruling party with 45 seats was toppled to 15 seats and the opposition with two seats gained 32 seats. The government was changed in Thimphu and the subsidy was reinstated after placing a pro-India party in power in Thimphu. The next election is on the calendar. It is time again to be cautious about how New Delhi will react to Bhutan’s road connectivity with its northern neighbour if it wasn’t with its nod.

If New Delhi accepts Bhutan’s move as a natural effort of its pet neighbour to boost its international leverage, everything will continue in comradeship.