ABSTRACT

The Himalayas is a serious victim of climate change. Consequences of the change will be the hardest for the people there. Residents in downstream will be no less affected. Melting ice and decreasing ice reserves indicate a disastrous future for those who rely on the Himalayas for water sources. The Himalayas are source of life for millions. Impacts are already visible in the form of flash floods, GLOF and unpredictable monsoon. Results are declining agricultural production, scarcity of water resources and deterioration of human health. Growing vehicular pollution, tourism and mega hydropower dams are some of the internal factors raising alarms in the Himalayas. Moreover, human activities in the vicinity of Bhutan not within its control are bigger influencers of climate changes.

Keywords: Carbon, climate change, glaciers, health, Himalayas rainfall, water, flood

Introduction

Bhutan sits on the southern slope of the Himalayas that is known for serene natural environment and pure air quality. The northern region of Bhutan is covered by snow throughout the year while its southern part is used for human settlement. Southern belt is suitable for agriculture and is the food basket of the country. Hilly region has sparse settlement except for the valleys. The capital Thimphu houses the largest congregation of population. Southern belt with tropical climate is home for a large population.

Quick changes in altitude and monsoon from the Bay of Bengal influence climatic conditions in Bhutan. Temperatures in Himalayan foothills of the southern belt ranges between 15-30 degree Celsius (59-86-degree Fahrenheit). The Inner Himalayas in central region has warm summers and cool and dry winters. This region has temperate and deciduous forests and fruit trees. Greater Himalayas in the far north is extremely cold and is mostly without vegetation.

Climate change

Climate change has become a cliché of our generation. The phenomenon is impacting not just a country but the whole human civilisation. Governments and authorities lack adequate commitments and resources to avert possible disaster of our generation that climate change may be bringing.

There are stark differences in understanding climate change. Political leadership and business tycoons have not yet accepted the idea while scientific research reports project towards natural catastrophe on earth if timely interventions are not made. Younger generation is engaged in this debate expressing concern over its future if current trend on climate change effect is continued. Greta-effect is taking children out of schools to demand that their future remains secure and safe.

Climate change in the Himalayas

According to WWF, over a billion people depend directly on the Himalayas for their survival, with over 500 million people in South Asia, and another 450 million in China completely reliant on the health of this fragile mountain landscape[2].

Climate change’s impact on Himalayan regions is phenomenal. The initial indications are melting glaciers and unpredictable seasonal rainfall. Many Bhutanese settlement downhill depend on Himalayas’ freshwater for farming and everyday use. If snow on mountain peaks melts completely this population faces higher incidence of diseases spread by mosquitos and floods, more frequent flash floods, forest fires and landslides.

Climatologists have warned that melting ice in the Himalayas is the sign of unpredicted climate disaster that may impact the entire settlement downstream and that too within our lifetime. The latest satellite pictures showing barren hilltops in Himalayas raise questions what made these ice melt in last few years (Wester et al., 2019). Being a mountainous country Bhutan will bear this brunt.

Result was not due to human activities in the last few years. Glaciers in the Himalayas started melting decades ago because of increased human activities. The rate at which it is melting now will have long-term impact on water, food and energy security in the region. Most significant impact of climate change in Bhutan is the formation of supraglacial lakes due to accelerated retreat of glaciers as a result of increasing temperature[3].

The black mountain tops mean threat at the bottom with melted ice joining the glacial lakes to produce Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF). Bhutan has already observed a few instances of this stark reality. Bhutan’s most devastating GLOF event was in October 1994 when Lugge Tsho burst killing 21 people, damaging 91 houses and 1781 acres of land (NCHM, 2019), killing animals and damaging farms. Of the 2,674 glacial lakes recorded in Bhutan, 24 have been identified by a recent study as candidates for GLOFs soon(Wangda, 2006). The phenomenon is likely to intensify in the coming years as more melted ice join these lakes. If left unchecked, it may wipe out the human settlement in the region in no time.

Bhutan invited international climatologists and environment conservationists following the Lugge Tsho disaster. Of many initiatives being underway currently, the biggest one is preventing burst of Lake Thorthormi in Lunana. In 2001, scientists identified Lake Thorthormi as one that threatened imminent and catastrophic collapse. Situation was eventually relieved by carving a water channel from the lip of the lake to relieve water pressure (Leslie, 2013).

Climate change impact in the Himalayas has immensely affected lives in foothills. Unpredictable weather conditions have caused havoc. It has become more difficult to predict and get prepared. The country is also increasingly experiencing prolonged and extreme droughts increasing the risk of loss of biodiversity, forest fires and reduction of crop yield and agricultural productivity.

The heavy rainfall brought about by Cyclone Aila in 2009 in Bhutan incurred loss of US$ 17 million (NCHW, 2019). The 2016 monsoon was much heavier than usual affecting almost all of Bhutan, especially in the south. Landslides damaged most of the country’s major highways and smaller roads. Bridges were washed away, isolating communities. Over 100 families were displaced.

Carbon Neutral

Bhutan is carbon negative and has committed to remaining carbon neutral. The country has constitutionally committed to have 60% forest cover at all time. These forest are the engines of Bhutan’s pleasant climate to this day. In all instances where Bhutan presented its commitment to climate change, the country received international appreciation. The country has many reserves that not only promotes green but wild animals too – protecting bio-diversity.

Today over 70% of Bhutan’s land is under forest cover (Pem, 2017). Absorption of carbon dioxide by these forests exceeds the amount of carbon dioxide produced by human activities. However, the country may not be an obvious place to look for lessons on addressing climate change (Dixon, 2015).

A 2013 World Bank report ‘Turn Down The Heat: Climate Extremes, Regional Impacts and the Case for Resilience’ predicted that even if the warming climate was kept at 2 degrees then this could threaten the lives of millions of people in South Asia. The region’s dense urban populations face extreme heat, flooding and diseases and millions of people could be trapped in poverty.

Bhutan declared in 2009 that it would remain carbon neutral and has made the most ambitious pledges on cutting emissions at COP21.But staying neutral as emissions from industry and transport rapidly rise will not be easy. It will require aggressively maintaining its tree cover and finding ways to grow economically in a carbon neutral or reduced way.

Figures show that Bhutan generates only 1.1 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), but the forest sequesters far more CO2 than this. This means they are a net carbon sink for millions of tonnes of CO2 each year. Additionally, Bhutan exports most of the renewable electricity generated by its fast-flowing rivers to India, driving the country into carbon negative status.

Protected areas are at the core of Bhutan’s national carbon neutral strategy. Currently 71% of Bhutan is under forest cover, and more than half the country is protected as national parks, nature reserves and wildlife sanctuaries – all connected by networks of biological corridors.

Bhutan utilises its extensive river resources to generate large amounts of renewable hydro energy, propelling the nation to carbon negative status. The government’s commitment to environmental protection is further evident in their provision of free electricity to rural farmers, investment in sustainable transport, support for the transition to an entirely and national programs Clean Bhutan and Green Bhutan.

However, challenges are mounting with population growth and increasing use of motor vehicles. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission from the transport sector could triple by 2030, if actions are not taken, an Asian Development Bank’s policy brief warns[4]. Pollutants from the neighbouring India also have negative impact on clear air of Bhutan. Harder days are near for Bhutan to remain carbon neutral and constitutional provision of 60% forest cover as forests depletes to wraths of climate change.

Causes

Too many motor vehicles

The country’s second national communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (NEC 2011) in 2011 reported that greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector accounted for about 20% of the country’s total emissions in 2000. By the end of 2012, this increased to about 30%.

Vehicle ownership grew by 9.28% in 2018 (MoIC, 2019). The growth was 9.15% in 2017 (MoIC, 2018) and 12.11% in 2016. Of the 100,544[5] vehicles registered in the country[6], over 52% are based in Thimphu. That gives us the big picture of why the capital city is growing warmer and polluted. The other industrial city Phuentsholing registers 34% of the vehicle ownership while other districts see very small numbers. Regional towns like Gelephu and Mongar have experienced growth in the last few years even though the numbers are small compared to Thimphu and Phuentsholing. Given the continued growth in vehicle ownership, GHG emissions from the transport sector are expected to grow further in coming years.

Major sources of air pollutants are passenger cars and heavy-duty vehicles, including diesel-powered large and medium-sized trucks and buses. They account for 73% of total vehicles in the country and were responsible for 70 to 90% of local pollutants and nearly 60% of GHG emissions.

Chart 1: Annual Vehicle Ownership Growth. Source: Road Safety and Transport Authority, RGOB

Hydropower projects

Bhutan’s ambitious project of harnessing 10,000 MW of hydropower by 2020 has raised some serious questions about the impact of dams on country’s biodiversity and pristine forests, social life and economy. Most megaprojects are built with large scale reservoir dams ignoring the fact that Bhutan’s fast-flowing river system provides opportunity to have run-off-the-river dams. Questions have also been raised about the safety of building so many projects in the fragile mountains of the Himalayas.

Projects like Sunkosh and Punatshangtshu I are already in troubles. The dams and tunnels associated to these projects are likely to cause catastrophic damage to the natural environment. The projects have also become financial burden for the country. The Sankosh Project will be the most expensive hydropower project at Nu. 115 billion while cost of Punatshangtshu I has escalated from initial assessment of Nu. 40 billion to Nu. 100 billion. The combined cost of two projects is more than current GDP of the country.

Bhutan relies on hydropower sales for economic sustainability. Built with loan from India, the country will face debt trap in case the power productions and water availability are affected by climate change in the Himalayas. Additionally, poor assessment of dam’s future impact on ecology, biodiversity and environment may cost bigger for Bhutan in longer run.

Mass tourism

Bhutan has a small tourism industry. The country was open to foreigners only in the recent decades. Several restrictive provisions still discourage many tourists visiting the country.

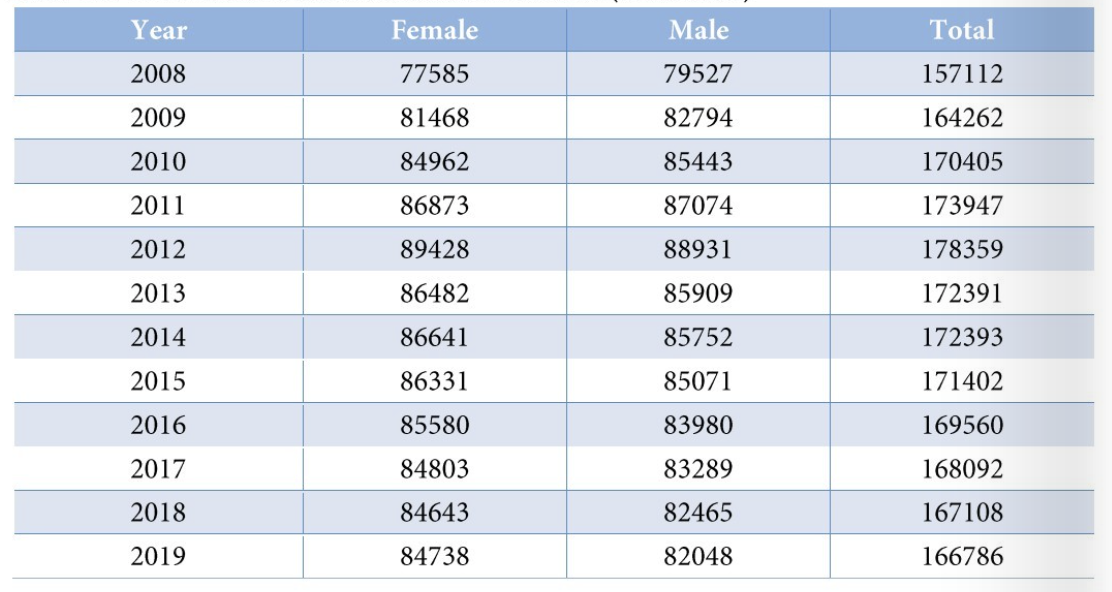

A total of 274,097 foreign individuals visited Bhutan in 2018 which is an increase of 7.61% over 2017. The number was around 100,000 in 2012. In 2018, international leisure arrivals grew by 1.76% to 63,367 over 2017 while arrivals from the regional market grew by 10.37% (TCB, 2018). However, many of them are regional tourists – mostly from India (70%). In last six years, regional tourists have increased by 400%. In 1974 when the country was formally opened to tourists, Bhutan welcomed only 274 tourists.

With increased arrival numbers, the country has more vehicles plying on the road. Plastics and other litters produced by these tourists are polluting the environment. The serene and quiet environment in temples, monasteries and sacred places is disturbed.

Impacts

Water resources

In 2016, flooding created panic in Thimphu. Phuentsholing -Thimphu highway was hit by flood in several locations. The highway carries food and fuel from India to half of Bhutan. The Kamji Bridge along the highway partially collapsed. The residents of capital city and nearby districts panicked of food and fuel shortages. Overall the floods drove down Bhutan’s gross domestic product by 0.36% (Tshering, 2018).

On the other hand, the country is increasingly facing water shortages. Climate change could be contributing to drying up of water sources. That is why growing cities like Thimphu (Seldon, 2019) and Phuentsholing are running short of water. In the rural areas, people have no water to drink and to irrigate their fields (Kuensel, 2018). Mismanagement of water resources means many wetlands have been destroyed and have disappeared (Wangchen, 2019). In early 2018, several households including Prime Minister’s residence in Thimphu had no drinking water supply for several days (Business Bhutan, 2019).

Almost all hotels in Thimphu face water shortage but hotels located in Norzin Lam are affected the most. Hoteliers appealed to the Thimphu thromde several times, but the situation remains same every year (Seldon, 2019).

Water sources in regional areas are also drying up. This is affecting drinking water supply and irrigation.

The government has not yet come up with any credible project on water management and addressing water shortages. It is very likely that land will dry up if interventions are not implemented quickly. This will have greater negative impact on agriculture and food security. When country already relies on import of substantial agricultural product from India, further dependence will derail economic growth. Income from hydropower sale may not suffice to sustain the national economy. (See Water of Bhutan by Govinda Rizal about Bhutan’s water sources and uses)

Agriculture

Big impacts of climate change are seen in agriculture sector. Bhutan’s Labour Force Survey Report 2016 shows 57.20% of Bhutanese depend on agriculture for survival (LMIRD, 2016). Agriculture contributes 16.52% to the national economy, as per National Accounts Statistics 2017 (NSB, 2017). The country has only 2.93% of the land suitable for agricultural cultivation (NSSC, 2011). Farming in hills and terraces have increasingly become challenging and difficult due to extreme weather conditions – as crops and tops soils are washed away and managing irrigation is very difficult.

Increasing temperature in the Himalayas is affecting the ecosystem and thus affecting agricultural productivity. Ecologically, farming in high elevation environments is unsustainable and more challenging due to large fluctuations and weather swings over the altitudinal gradient (Chapin et al 2005).

There is need for Bhutanese to have access to facilities of farming technology and techniques that help agricultural production adapt to and tolerate the changing temperature. Considering shorter monsoon prediction, Bhutan must improve irrigation infrastructures and water management practices. A recent study in Bangladesh revealed that adoption of climate-smart agriculture has improved the food security of the coastal farmers (Hassanet al, 2018).

Weather & natural disaster

Country’s mean temperature and precipitations is on increasing trend (NEC, 2006). It matches the findings of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which reported rising global land and ocean temperature by 0.85°C over the period 1880–2012 (IPCC, 2013).

A simulated projection of temperatures in South Asia shows rising trends in temperature and precipitation in both winter and summer with large anomalies in monsoon (Table 1). This model has predicted the mean summer and winter temperature increases of 2.8 °C and 2.1 °C, respectively, over 2040–2069 (NEC, 2011). ICIMOD says warming has been quicker in higher altitudes (Bajracharya et al, 2017) which ultimately means Bhutan will face wraths of climate change quicker than its low land neighbours.

Unpredictable weather means the country is on red line to face natural calamities from flood, drying water sources and GLOF bursting which we have already discussed above.

Table 1. Bhutan Vs South Asia temperature projection

| Parameters (Mean) | Projections for Bhutan | Projections for South Asia |

| Annual temperature | Increase by 2.1-2.40C over 2040-2069 | Increase by 1.3-3.50C in 2100 |

| Summer temperature | Increase by 2.80C over 2040-2069 | Increase by 20C in 2100 |

| Winter temperature | Increase by 2.10C over 2040-2069 | Increase by 2.550C in 2100 |

| Annual precipitation | Increase by 20% over 2040-2069 | Decrease by 3%(min) & increase by 39% (max) in 2100 |

| Monson precipitation | Increase by 350-450mm/season from 1980 to 2069 | Decrease by 7% (min) and increase by 37% (max) in 2100 |

| Winter precipitation | Decrease by 5mm/season from 1980 to 2069 | Decrease by 14% (min) and increase by 28% (max) in 2100 |

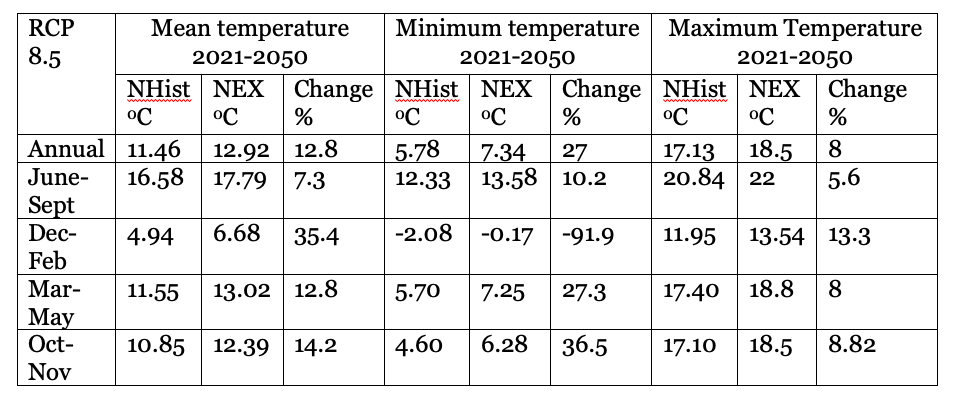

Table 2. Annual & seasonal mean temperature projection under RCP 8.5

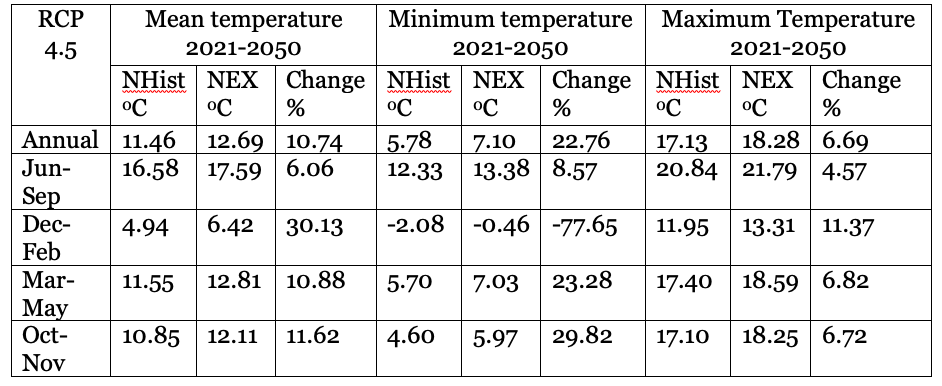

Table 3. Annual & seasonal mean temperature projection under Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5

Source: Analysis of Historical Climate and Climate Projection for Bhutan, National Centre for Hydrology and Meteorology, RGOB

Human health

WHO has put impact of climate change on human health into three main categories: (i) direct impacts of for example, drought, heat waves, and flash floods, (ii) indirect effects due to climate-induced economic dislocation, decline, conflict, crop failure, and associated malnutrition and hunger, and (iii) indirect effects due to the spread and aggravated intensity of infectious diseases due to changing environmental conditions (WHO, 2005).

WHO said increase in temperature would spread vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue and water-related diseases such as diarrhoea. Dengue has been observed almost like epidemic in recent years in Bhutan (BNN, 2019).

It is projected that spread of malaria, Bartonellosis, tick-borne diseases and infectious diseases linked to the rate of pathogen replication will all be enhanced. Malaria spreading mosquitoes have recently been observed at high altitudes in the region (Eriksson et al, 2008).

Simple instances such as these suffice the impact of changing climate in Bhutan. In late 80’s, early 90’s, Thimphu resident never needed cooling. Now, it’s become like a requirement – air conditioning and ceiling fans have become necessity in the capital city. The snowfall has become unpredictable.

Preventive measures

Bhutan and the neighbouring countries in the Himalayas must come up with practical approaches to ad[7]dress ever-increasing negative impact of climate change in the region. Because the impact on Himalayas is observed to be much faster than lower altitude, it is an urgency for the country to think seriously how the impact can be reduced.

ADB has recommended to upgrade fuel quality testing procedures, vehicle emission standards and revise its standard from Euro 2 to Euro 6. It also recommended to restrict diesel cars and light duty vehicles.

“It would also be necessary for Bhutan to improve its regulations, strengthen enforcement, and enhance the testing procedures and execution to minimize errors and prevent high-emitting vehicles from passing the vehicle emission inspection test,” the report stated.

In Bhutan, diesel vehicles comprise only 40% of the total number of vehicles in use, yet they are the largest polluters, contributing 98% of PM, 95% of nitrogen dioxide, and 87% of sulphur dioxide emissions in the country.

Another suggestion is to promote low-carbon vehicles like Hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and electric cars. The government’s plans to tap international climate finance could go well with low-carbon commercial vehicle strategy, favouring electric mobility and focusing on taxis, buses, and urban freight vehicles.

The first elected government led by Jigmi Yosher Thinley had made efforts to put restriction on number of vehicles being imported. The attempt was crushed. Tobgay government in 2017 withdrew from the free vehicular movement agreement among Bhutan, Bangladesh, Indian and Nepal. The newly elected government in 2018 said it will relook into the agreement but has not given priority. Bhutan must formally withdraw from the agreement if the country is serious about reducing pollution.

Despite ADB recommendations, Bhutan’s diesel consumption and vehicle imports continue to increase posing threat to Bhutan’s status of a carbon neutral country (Dema, 2019). Cities are already feeling the pressure to accommodate ever increasing vehicle numbers (Wangmo, 2019).

Bhutan stepped up its response to climate change with the launch of a project to advance its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) focused on water. The project, to be implemented with the support of the UNDP, benefits from a US$ 2.7 million grant from the Green Climate Fund, a fund created under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to support the efforts of developing countries to respond to the challenges of climate change (UNDP, 2019).

In an effort to resolve water scarcity and reduce human wildlife conflicts, Tarayana Foundation operates ‘Developing climate resilient communities through appropriate adaptation and mitigation interventions’ in 15 villages of five districts – Lhuentse, Mongar, Sarpang (Sarbhang), Samtse (Samchi), and Haa. The project supplements the NAP.

The project supports interventions such as community mobilisation, training on watershed and land management, clearing of water sources, plantation of suitable plants around water sources to recharge the water table, installation of rain water harvesting tanks, and construction of water reservoir tanks would be undertaken.

Ugyen Wangchuck Institute of Conservation and Environment (UWICE) runs Himalayan Environmental Rhythms Observation and Evaluation System (HEROES) project in close collaboration with schools and nature clubs across the country. The project employs a combination of weather data collection and citizen science to help understand climate change. Project encourages hundreds of students to actively engage in observing their immediate environment to detect changes in how plants and wildlife respond to climate change. Some 34 teachers and 340 students have been trained and are now participating in the project[8].

With the effects of climate change intensifying, the frequency of significant hydro-meteorological hazards are expected to increase. To that end, Bhutan is partnering with development institutions including the World Bank, to strengthen its hydrological and meteorological services and better preparedness for disasters[9].

The project will pioneer flood forecasting and weather advisories to help farmers increase their crop yields—a first in Bhutan—and enhance weather forecasting and disaster management.

Bhutan made the world’s most far-reaching climate promise to the Paris climate summit, a climate research group says[10]. The group appreciated Bhutan’s efforts to keep the country green and highlighted Bhutan’s world record on planting new trees – nearly 50,000 trees were planted in an hour in 2014.

Conclusion

The efforts must continue to keep alive Bhutan’s serene ecology and air quality. Efforts within the country to act swiftly on vehicular pollution, managed tourism programmes and efficient use of water resources are some of the steps Bhutan must take at its discretion whereas there is more to do in collaboration with neighbouring countries like China, India, Bangladesh and Nepal in designing programmes to minimise climate change impact on the Himalayas.

References

Asian Development Bank (2019). Bhutan vehicle emission reduction road map and strategy, 2017–2025, ADB Briefs, No 110 July 2019. Retrieved in October 2019 from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/513931/adb-brief-110-bhutan-vehicle-emission-reduction-strategy.pdf

Bajracharya S. R., Maharjan S. B. & Shrestha, F. (2017). The status and decadal change of glaciers in Bhutan from the 1980s to 2010 based on satellite data. Annals of Glaciology 55(66), 159-166, Cambridge University Press; doi: 10.3189/2014AoG66A125

Chapin F. S., Sturm M., Serreze M., McFadden J., Key J., Lloyd A., (2005). Role of land-surface changes in Arctic summer warming. Science, 310(5748), 657-660. DOI: 10.1126/science.1117368.

Dema, C. (28 September 2019). Vehicular emission, a cause for concern. Kuensel daily. Retrieved in October 2019 from http://www.kuenselonline.com/vehicular-emission-a-cause-for-concern/

Dengue is epidemic. (7 September 2019). Bhutan News Network. Retrieved in October 2019 from http://www.bhutannewsnetwork.com/2019/09/dengue-is-epidemic/

DIXON, A. (11 December 2015). World Bank blogs. Retrieved in August 2019, from End Poverty in South Asia: http://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/big-lessons-climate-change-small-country

Editorial (18 June 2018). Water shortage in water abundant Bhutan?, Kuensel Daily, Retrieved in October 2019 from http://www.kuenselonline.com/water-shortage-in-water-abundant-bhutan/

Editorial. (8 January 2019). Water crisis. Business Bhutan. Retrieved in October 2019: https://www.businessbhutan.bt/2019/01/08/water-crisis/

Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (03 December 2015). ECIU Comparator Tool reveals surprising results, Retrieved in October 2019 from https://eciu.net/news-and-events/press-releases/2015/comparator-tool

Eriksson M., Fang, J., Dekens, J. (2008) ‘How does climate affect human health in the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region?’, Regional Health Forum

Hasan M. K., Desiere, S., D’Haese, M., Kumar, L. (2018). Impact of climate-smart agriculture adoption on the food security of coastal farmers in Bangladesh. Food Security 10(4).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2013). Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of the working group I to the fifth assessment report of the IPCC. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Labour Market Information and Research Division (2016). Labour force survey report 2016. Department of Employment and Human Resources, MoLHR Thimphu, RGOB.

Leslie, J. (17 June 2013). A torrent of consequences. World Policy Journal, Summer (2013).

Ministry of Information and Communication (2019): Info-comm and transport statistics 2019, Thimphu, RGOB. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://www.moic.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/10th-Annual-Info-Comm-and-Transport-Statistical-Bulletin-2019.pdf

Ministry of Transport and Communication (2018). Info-comm and transport statistics 2018. Thimphu. RGOB. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://www.moic.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Annual-Info-Comm-and-Transport-Statistical-Bulletin-2018.pdf

National Centre for Hydrology and Meteorology (NCHM) (2019). Analysis of historical climate and climate projection for Bhutan (2019). Thimphu; Royal Government of Bhutan

National Environment Commission (2006). Bhutan national adaptation programme of actions. MAF, RGOB.

National Environment Commission (2011). Second national communication to the UNFCCC. MAF Thimphu, RGOB.

National Soil Services Centre (2011). Bhutan land cover assessment 2010—technical report. MAF & MoF Thimphu, RGOB.

National Statistics Bureau (2017). National accounts statistics 2017. Thimphu, RGOB.

Pem, S. (7 February 2017). Bhutan’s 71 percent forest cover confirmed, Bhutan Broadcasting Service. Retrieved in October 2019 from: http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=67069

Seldon, P. (1 May 2019). Thimphu gets a record low of -8 as water crisis continues, The Bhutanese weekly. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://thebhutanese.bt/thimphu-gets-a-record-low-of-8-as-water-crisis-continues/

Seldon, P. (16 March 2019). Thimphu hotels hit with water shortage due to drying sources in Motithang. The Bhutanese Weekly. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://thebhutanese.bt/thimphu-hotels-hit-with-water-shortage-due-to-drying-sources-in-motithang/

Tourism Council of Bhutan (2018). Bhutan tourism monitor 2018, Thimphu, Royal Government of Bhutan,

Tshering, D. (1 October 2018). World Bank blogs: building up Bhutan’s resilience to disasters and climate change. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/building-bhutan-s-resilience-disasters-and-climate-change

United Nations Development Programme (2019), Bhutan pursues climate resilience with National Adaptation Plan, Retrieved from https://www.bt.undp.org/content/bhutan/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2019/bhutan-pursues-climate-resilience-with-national-adaptation-plan.html

Wangchen, J. (28 January 2019). Drying up of water sources, a major concern. Business Bhutan Weekly. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://www.businessbhutan.bt/2019/01/28/drying-up-of-water-sources-a-major-concern/

Wangda, D. (2006). GIS tools demonstration: Bhutan glacial hazards. Proceedings of the LEG Regional Workshop on NAPA coordinated by UNITAR. Thimphu: Deptartment of Geology and Mines, RGOB.

Wangmo, C. (28 September 2019). Too many cars, too little space. Kuensel daily. Retrieved in October 2019 from: http://www.kuenselonline.com/too-many-cars-too-little-space/

Wester, P., Mishra, A., Mukherji, A., Shrestha A. B. (2019). Ed. The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment – 2019: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Kathmandu, ICIMOD, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-92288-1.pdf

World Bank (2018). South Asia Hydrology Forum Report. Retrieved October 2019: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/194171554125112686/SAFH-Report-final.pdf World Health Organisation (2005). Human health impacts from climate variability and climate change in the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region, Report from an Inter-Regional Workshop, Mukteshwar, India.

[1] 1Adelaide, Australia

[2] Melting Mountains: Climate Change and the Himalayas, WWF, retrieved on 18 Oct 2019 from https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/eastern_himalaya/threats/climate/

[3] Climate Change Adaptation, UNDP Bhutan, retrieved from https://www.adaptation-undp.org/explore/bhutan

[4] Bhutan Vehicle Emission Reduction Road Map and Strategy, 2017–2025, ADB Briefs, No 110 July 2019. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/513931/adb-brief-110-bhutan-vehicle-emission-reduction-strategy.pdf

[5] This figure is as of 31 December 2018.

[6] There are 103,814 cars in the country as of July 2019, according to the Second Quarterly Info-Comm and Transport Statistics 2019

[7] Bhutan Vehicle Emission Reduction Road Map and Strategy, 2017–2025, ADB Briefs, No 110 July 2019. Retrieved October 2019: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/513931/adb-brief-110-bhutan-vehicle-emission-reduction-strategy.pdf

[8] Understanding Climate Change in Bhutan. Bhutan Foundation. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://bhutanfound.org/projects/understanding-climate-change-in-bhutan

[9] South Asia Hydrology Forum Report. World Bank. Retrieved in October 2019 from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/194171554125112686/SAFH-Report-final.pdf

[10] ECIU Comparator Tool reveals surprising results, Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit, 03 December 2015. Retrieved in October 2019 from https://eciu.net/news-and-events/press-releases/2015/comparator-tool

2 thoughts on “Climate Change Impact in Bhutan”

Comments are closed.